|

Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira

Foreword of Genazzano

|

|

|

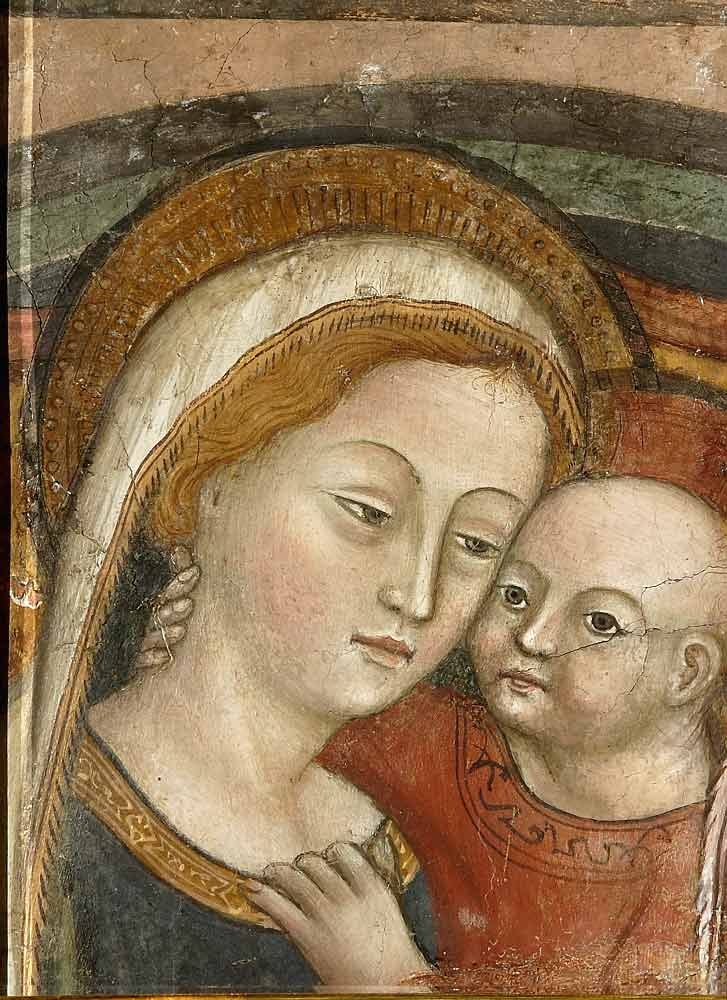

SEVERAL reasons prompted my joyful agreement to write a foreword for this book at the request of its author, whom I dearly esteem. Foremost, it is a book about Our Lady, whose greatness I have not ceased to exalt throughout my life and will continue to exalt until my last moment. Secondly, the author of the work is one of my most dedicated collaborators in the great fight in which the Brazilian TFP (as well as each of the other autonomous 15 TFPs) is engaged—a struggle against the fundamentally atheistic and pantheistic egalitarianism (1) that is increasingly dominant in contemporary society. There is yet a third reason—a strictly personal one, which I cannot pass over in silence. In 1967, as a part of my daily routine, I began to read a book about Our Lady of Good Counsel.(2) How I came upon it I do not recall, but I read it very late at night while lying in bed awaiting the onset of sleep after days filled with arduous effort. The reading of that book brought me a gentle and discreet spiritual joy—something infrequent for me. I felt this even when the author digressed on some matters very indirectly related to the subject of his excellent book. Those movements of my soul were, however, so discreet that I paid little attention to them. Nevertheless, the recounting of the impressive facts which constitute the history of the invocation and painting of Our Lady of Good Counsel led me to ask a friend with contacts in Italy to obtain a picture of it for me. Shortly thereafter I fell seriously ill, so much so that I was hospitalized and underwent a serious operation. While recovering with promising speed, circumstances of a different nature caused my soul distressing concerns. It was at this time that some friends brought the requested picture to me in the hospital. I must say that I had virtually forgotten about Monsignor Dillon's excellent work by then. The friends who had gathered around my hospital bed unwrapped the picture. I gazed at it with natural and respectful attention when—wonder of wonders!—something most indescribable happened. It absolutely could not be called a miracle. The picture had not been sensibly altered; the figures and colors of Our Lady of Genazzano and the Infant Jesus she held in her arms were unchanged. However, I had the surest impression that the figure of Our Lady gazed at me with moving kindness, while it expressed (in a way I do not know how to explain) something that in a serene and irrefutable way luminously resolved the problems of my soul, which were far more tormenting than those of my body. I did not mention this to any of those present at the time. When I commented on the occurrence later, two friends who had been present affirmed that they had perceived no change in me but only in the image that gazed at me with merciful love. Since then, I have been bound to the image of Our Lady of Genazzano by an indescribable debt of gratitude. To fulfill that debt, I began to relate the incident to my courageous and devout battle companions. Later, at the behest of the Augustinian Fathers of Genazzano, I decided to recount the story in the magazine that they publish in the city of the Mother of Good Counsel. (3) * * * Having said this, let me state the essential facts about that august image. Religion was seriously threatened in fifteenth-century Albania. On one hand, the fervor of the Catholic populace was declining; on the other, hordes of Mohammedan invaders were assaulting the country, intent upon destroying the Catholic faith to its very roots. To prevent this catastrophe, Divine Providence raised up a hero comparable in courage and faith to Charlemagne's peers or the outstanding warriors of the Crusades and the Spanish-Portuguese Reconquest. His name was Scanderbeg. While he lived, performing heroic and glorious feats, Albania resisted. When he died, Albania's resistance crumbled—a fitting punishment for a population steeped in lukewarmness. In addition to Scanderbeg, and far superior to him, there was another pillar of shaken Christendom in Albania: a fresco of Our Lady then known as "Our Lady of Good Services." (This title is analogous to Our Lady Help of Christians, a devotion that has spread throughout the Catholic world.) Since the picture was located in a shrine near Scutari, Albania's capital, it was feared that this source of so many precious graces for even so lukewarm a people would fail into the hands of the Mohammedan invaders. This was precisely the fear felt by two devout Albanians, Georgio and De Sclavis, worthy representatives of the country's faithful remnant. The solution to this predicament was not long in coming. Before the very eyes of astonished devotees, compatriots of the great Scanderbeg, the fresco slowly detached itself from the wall. It rose and began to move in the direction of the Adriatic Sea and never varied in its course. At the same time, Our Lady made the two Albanians understand that she wanted them to follow her image. With a faith and moral fiber like that of Scanderbeg, they did not hesitate. They walked miraculously over the water until the image reached most Catholic Italy. Consider the synthesis of events narrated to this point: a world falling victim to its own moral and religious crisis rather than to the strength of a terrible enemy; two faithful who believe and continue to hope against all hope; then a stupendous miracle that crowns their perseverance. These facts merit our attention even in their details and are related further on by the author, João Scognamiglio Clá Dias, in a fluent style, full of piety and enthusiasm. (4) These qualities of soul are evident throughout the text, with the savory repetition of divers concepts contributing to this. Even up to our days, a recurring characteristic can be observed in the anecdotes about the devotion to the Mother of Good Counsel of Genazzano: the faithful who come to her feet beseeching her assistance are in the midst of bewildering and distressing trials. Such was the situation shared by Georgio and De Sclavis, the two heroes chosen by Our Lady to be her mortal escorts in crossing the Adriatic, and an elderly Italian woman, Petruccia, whose brave soul was proportional to theirs. Indeed, while the Albanians followed her image across Italy, Our Lady suddenly disappeared from their sight. It had gone to fill the soul of Petruccia with heavenly consolation at a time when she was at the height of trial and adversity. It is opportune to say a word about this woman, a great example of the strong woman of the gospel, who was chosen by Our Lady to build the most blessed shrine where her image has been exposed for the veneration of countless faithful for five centuries. Petruccia was a devout, rather well-to-do widow. She had been favored with a vision in which the Blessed Virgin entrusted her with the mission of restoring the church of Our Lady of Good Counsel in Genazzano, which had fallen nearly into ruin. (5) To that end, Petruccia sought out the charity of the faithful of the town. Their response left much to be desired, so the alms she collected fell short of what was required to finish the work on the church. Not lacking in courage, she decided to apply the remainder of her inheritance to the reconstruction project. Even this proved insufficient, leaving the work far from completion. This failure provoked sarcasm from the very population that had been so lukewarm in its response to her pleas for financial help. Petruccia, despite her eighty years, remained enthusiastic, nevertheless, trusting firmly in the help of the Blessed Virgin. What an immense and marvelous surprise it was both to her and the townspeople when on the evening of Saturday, April 25, 1467, a cloud of striking appearance drifted down upon the village. Emanating from the cloud was the sound of equally striking and beautiful music. Slowly, the fresco of Our Lady separated from the cloud and positioned itself on the altar that Petruccia had ordered in anticipation of the church's complete restoration. Blessed Petruccia's earlier vision was confirmed. The Blessed Virgin obviously desired the completion of the work. From then on, the townspeople, who ran in awe to pay homage to the image, contributed most generously to the quick and final reconstruction of the church. There, while the faithful today venerate the picture of the Blessed Virgin and Child (marvelously transported from Scutari by angels), the mortal remains of Blessed Petruccia sleep the sleep of peace awaiting her final resurrection. The two Albanians, baffled by the painting's disappearance and ignorant of its appearance in Genazzano, were wandering about Italy in futile search of their lost treasure. When news of the events taking place in Petruccia's village finally reached them, they hastened there. One can easily imagine their wonder and rejoicing upon finding the heavenly painting. They attested that the picture that excited all Genazzano was one and the same as that formerly venerated in Scutari, and thus their mission as witnesses was fulfilled. Both Georgio and De Sclavis remained in Genazzano and each eventually married. To this day, descendants of Georgio still live in the town. It is self-evident that the mission of the two Albanians was intimately connected with that of Petruccia. Under the maternal direction of the Blessed Virgin, all three struggled and overcame all manner of obstacles and trials until the glorious completion of a common goal. * * * We can draw from this story a lesson for our own century, corrupted like fifteenth-century Albania by the religious and moral decadence which is the starting point for all other forms of contemporary decadence. In 1917, the Blessed Virgin appeared to three shepherd children of Fatima. She entrusted them with the duty of communicating her message of justice and mercy to the world: If mankind did not convert and if the world was not consecrated to her by the Holy Father in union with all the bishops simultaneously in their respective dioceses, the world would be ravaged by terrible punishments. Impiety and immorality would thus be duly chastised and, consequently, vanquished. "Finally," the Blessed Virgin concluded, "my Immaculate Heart will triumph." It stands to reason that during that time of trial, Divine Providence will not fail to raise up strong and generous souls in the Church, somehow making His designs known to them and using them in one way or another to obtain His victory. When the events predicted at Fatima are spoken of, attention is focused mainly on the future punishments and on those who will suffer them. Indeed, the privileged devotees of the Blessed Virgin that she will raise up seem all but forgotten. Who will they be? My own conjecture is that they will be in the minority but will be recruited from among persons of the most varied nationalities and social conditions from all corners of the globe. Each one, according to the manner and degree chosen by Mary Most Holy, will be the recipient of admirable graces, will face terrible obstacles, and will at times consider himself to have failed completely. Yet, on the day of the great triumph, each will be marvelously convoked to take part in the glorification of the Blessed Mother of God and to live during at least the first days of that glorious Marian era eloquently foreseen by Saint Louis Marie Grignion De Montfort, the great seventeenth-century apostle of Mary Most Holy. (6) I have those souls of fire in mind as I write this foreword. Thus, I would be pleased if my words incline them to an attentive reading of this excellent book of João Clá Dias, through which they may be led to beseech more courage during the great trials they will encounter, courage they may surely obtain. Notes: (*) “The Mother of Good Counsel of Genazzano”, João S. Clá Dias, Western Hemisphere Cultural Society, Inc., Penn., 1992, pages XVII-XXV (1) The atheistic character of egalitarianism is brilliantly demonstrated by Saint Thomas Aquinas when he states: "We must say that the multitude and distinction of things come from the intention of the first agent, Who is God. For He brought things into being in order that His goodness might be communicated to creatures, and be represented by them; and because His goodness could not be adequately represented by one creature alone, He produced many and diverse creatures, that what was wanting to one in representation of the divine goodness might be supplied by another. For goodness, which in God is single and uniform, in creatures is manifold and divided; and hence the whole universe together participates in the Divine goodness more perfectly, and represents it better than any single creature whatever" (Summa Theologica, I, q. 47, a. 1). (2) He refers to The Virgin Mother of Good Counsel by Monsignor George F. Dillon, apostolic missionary in Australia, in its French translation, La Vierge Mère du Bon Conseil (Bruges: Desclée de Brower, 1885). (3) "Una Dichiarazione," Madre del Buon Consiglio, Genazzano, July-August 1985, p. 28. We have reproduced this text on pages 122-123. (4) See Chapters 4 and 5. (5) A bas-relief has been venerated in this church since the fourth century under the invocation of Our Lady of Good Counsel. Petruccia began her reconstruction with one of the side chapels that is dedicated to Saint Blaise; it is against the principal wall of this chapel that the venerated fresco from Scutari came to rest. (6) Saint Louis De Montfort was born in 1673 in Montfort-sur-Meu, France. Ordained in 1700, he entered heaven in 1716. Leo XIII declared him blessed on January 22, 1888, and Pius XII canonized him on July 20, 1947. |

|