|

Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira

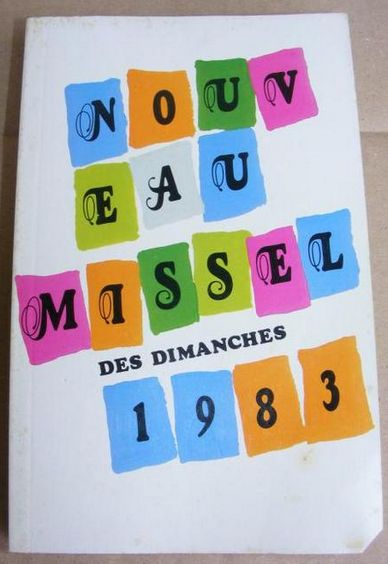

Marx and Luther in the New French Missal

“Folha de S. Paulo”, 13th September 1983 |

|

|

FRANCE, first-born daughter of the Church, was brilliant down through the centuries in the acts of its illustrious children in favor of the preservation and expansion of the Mystical Body of Christ.

It is precisely in France that the "New Sunday Missal — 1983" is circulating widely and with impunity. The work, carrying the Imprimatur (6/26/82) of Msgr. R. Boudon, Bishop of Mende and President of the French Language Liturgical Commission, has not been condemned so far. Its pages thus continue to intoxicate countless French-speaking faithful seeking there the invaluable inspiration of liturgical texts that conform to the perennial teaching of the Church, but also finding texts profoundly discrepant from the Catholic spirit. Here I will limit myself to comment on three characteristic topics of the Nouveau Missel. At the end of the Mass for Sunday, March 13, page 139, the "New Missal" says this of... Marx! Yes, you are not mistaken, Karl Marx: "One-hundred years ago in London, on March 14, 1883, the death of Karl Marx, German economist and philosopher. Some people will be surprised to find the best-known representative of modern atheism mentioned in a missal. But the repercussion of the movement he started has so much importance that this event cannot go by in silence. Although Marxist atheism was condemned by the Popes many times, the evaluation of Marxism's socio-economic analysis lies in the jurisdiction of human sciences. There are many interpretations of Marx's thinking. The most current, and the official one in Marxist states, continues to regard religion as an alienation from which man must liberate himself." Everything about this passage is appalling. If the mere importance of a man's work justified his being mentioned in a book made for the faithful to follow the liturgical ceremonies, then the Missal should remind the faithful of the whole gallery of great malefactors of history. So, given that the Incarnation and the Redemption were historical facts infinitely more important than Marxist expansion, in light of these two events all those who deeply influenced the world in a negative sense would also deserve to be brought to mind by the Missal, and much more so than Marx. To speak only of the New Testament, Judas, Pilate, Herod, Annas, Caiphas, the interminable series of celebrated heretics, famous apostates and sinners whom scandal immortalized should also be remembered. Not only remembered, but focused upon with the neutrality tinted with sympathy the Missal has in discussing Marx. Sympathy, yes, that goes so far as to say that Marx's socio-economic doctrine lies outside the jurisdiction of the Magisterium of the Church, that is, that there is no incompatibility between Catholic Doctrine and the Marxist regime, but only between it and Marxist atheism, which is obviously inexact. This attitude is all the more appalling since one reads in the Missal's introduction (p. 4): "When our commentaries show sympathy for the ideas of some person or movement, it is because there can be found a latent cornerstone of the Gospel." Should one therefore conclude that Marx and Marxism are "cornerstones of the Gospel"? Since the ideological and historic ancestor of atheism was Protestantism (Cf. Leo XIII, Encyclical Parvenu à la vingtcinquième année, 1902), it is no wonder that the new Missal also placed in its pages Luther, the archetypical heretic. In the "Week of Prayer for Christian Unity" (p. 81), it says: "Five hundred years ago, on November 10, 1483, in Eisleben, Saxony, the birth of Martin Luther, whose destiny (sic) was to weigh so heavily on the unity of the Church. " The word "destiny" here seems to have a strange, fatalistic connotation, as if to exculpate the heresiarch of responsibility for his schism and fight. Even more significant is the mention of Luther in the week of July 6-12 (p. 493): "Five hundred years ago, on November 10, 1483, the birth of Martin Luther. Augustinian monk, doctor of theology, he gave emphasis to the Paulist doctrine of justification by faith, which would become the cornerstone of Protestantism: faith alone saves, not works. Scandalized by the selling of indulgences and abuses of the Church, Luther published his great writings of reform against Roman supremacy, the sacraments (except Baptism, the Eucharist and Penance), and the concept of a visible church. His positions were condemned by Pope Leo X, he was banished from the Empire, and his writings were prohibited and burned. He spent the rest of his life, until 1546, defending his theses and organizing his Church ... With the passing of time, it is licit for us to regret that this revolt, motivated to a great extent by the situation of the Church at that time, developed into a rupture between Christian brothers." The text could not be more severe with the Church or more full of poorly-veiled sympathy for Luther. This is true to the point that in the last sentence the reader doesn't know who is to blame for the rupture, the heresiarch with his denials, or Holy Church with Her condemnations. There is much more that could be noted in this tragically censurable Missal. Here I will restrict myself to evoking the thousands of faithful who assist at Mass with the book in hand and, genuflecting, commemorate Luther the heresiarch and Marx the arch-atheist in terms replete with benevolence. This seems to me a thousand times more tragic than the nuclear danger, the international financial crisis, or anything else.

|

|