|

Plinio Corręa de Oliveira

Saint Odilo of Cluny’s Personality True Humility Is Respect for Oneself and Others

Saint of the Day, Saturday, September 23, 1972 |

|

|

Each epoch has its great men. Saint Odilo was a great man characteristic of the Middle Ages: a great man in the true sense of the word, in whom we note the conjunction of eminent holiness and extraordinary personal qualities. He was a man of great personal worth on the human plane and adorned with supernatural graces incomparably more precious than any personal worth, with a breadth, grandeur, and harmony you do not find in the great men of the time of the Revolution. It is interesting to see the description of Saint Odilo’s life and personality because we will see proven once again the thesis we expounded once when commenting on Our Lady of Jazna Gora. If Saint Odilo lived in our days, he obviously would be a topnotch ultramontane. Clearly, all genuine and authentic figures of the Constantinian Church ── therefore, the Catholic Church tout court, which is the same thing—and especially the canonized saints whom She infallibly declares to have been perfect followers of her spirit and observers of her law ── are all perfect counterrevolutionaries in one way or another. This thesis will make us love the Church more and more and understand the vital, profound, irreplaceable nexus between the Holy Church and our vocation, so I want to develop it with full attention. The text on St. Odilo says:

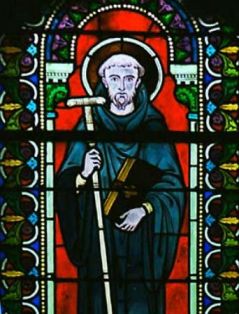

Let us start with his minor merits. He had a grave gait, an admirable voice, and spoke well. It was a joy to see him. His face had an angelic countenance; his gaze had extraordinary serenity. His every movement, gesture, and action expressed honesty. These are his lesser merits, more signs of virtue than virtue itself. They describe the saint’s demeanor and way of being. Saint Odilo’s entire way of being was full of composure and dignity Note that in the old French in which the text is written, the word honesty is not the virtue we usually call honesty now, which is to respect someone else’s property. In those days, honesty meant composure. Un honnęte homme was a very composed and dignified man. Saint Odilo’s whole way of being was full of composure and dignity. Every fold of his priestly habit had an air of dignity and reflected respect for himself and others. On the folds of his cassock, you could see his respect for himself and others. In order to understand this well, it is interesting to analyze this typical priest of the Catholic Church whom she canonized for perfectly expressing her priestly ideal. There is no comparison with a progressive priest going around without priestly garb or dressed like a playboy; this is an abomination. A little treatise on the various ways of walking What is a grave gait? It is a firm, manly step that indicates the attitude of soul of a resolute man who takes action. He masters every piece of ground he steps on. His is a serious gait of a man who wins when he walks forward even without visible obstacles in front of him. He walks like someone who would face anything. His gait is consequential and fully deliberate. The way people walk defines them a lot. You could almost do a little treatise on the various forms of walking. There are people with frivolous gait. You can see from afar that they are aimless. They can go to either side of the sidewalk at any time or avoid the street. They have no bearings. Their steps show an unstable, frivolous, immature mentality that changes course at any moment. There are gaits of soft people. You have the impression the person carries his legs instead of being carried by them. His legs land in a soft and bashful way or spread out, leaving the impression they are cartilaginous and left behind while the person lazily advances. Then there are effeminate gaits lacking solidity or vigor, missing manliness. There are also ‘mega’ gaits whereby you notice the person has no resource other than his feet to draw attention to himself. He hits the floor hard and makes a fuss with his feet to disguise the nullity of his countenance. That is his recourse. Horses—not to mention more prosaic animals—have twice as many. You also have streetsmart, quick little steps that slither. It is fascinating to pay attention to people’s gaits. Let those of you who have done a methodical examination of people’s steps raise your hands to satisfy my curiosity. Three... You have not wasted your time! A person’s gate says a lot, which is why this biographer, a contemporary of Saint Odilo, who knew him closely, decided to begin by describing his gait. St. Odilo’s voice, angelic countenance, and elegance On the other hand, you can see how St. Odilo’s voice accompanies his gait. Here is his extraordinary comment about St. Odilo’s voice: He had an admirable voice and spoke well; it was a joy to see him. Why? Because his angelic face reflected serenity. Note what ‘angelic’ meant in the Middle Ages. It was not the irresponsiblelooking chubby little angels like those on the altar in the chapel of the seat of the Reign of Mary. It is no compliment for a man to have that little face. The medieval angels were Fra Angelico’s. Great heroes of heaven, princes in the presence of the Most High, recollected, contemplative, supereminent in intelligence and will. They are the angels of medieval stained glass. Such was the angelic face of Saint Odilo. He had an angelic face, an angelic voice, and an angelic gait. He had real elegance, which does not necessarily mean wearing a very wellcut outfit, let alone being very fashionable. It consisted of communicating his spirit’s splendor to his bearing and attire. That is the true notion of elegance. He had a radiance of spirit, personality, and, without realizing it, communicated it to his clothing. Some people have this gift. His wellkept cassock and its every crease reflected his respect for himself and others. True humility is respect for oneself and others True humility is respect for oneself and others because it is to respect each person as he should be and respect oneself as one should. St. Odilo knew he was a saint. He knew he was the soul of the great Cluny movement, which was the soul of the Middle Ages, so he was the radiant soul of the Middle Ages. Abbot and superior of a religious order, a priest and monk, consecrated by God, he knew all this and respected himself enormously. Respecting yourself is not being mega. Being mega is using yourself to show off. It is not respecting yourself. The opposite of a mega person, St. Odilo respected himself enormously and, at the same time, respected others a lot. St. Teresa says the Church repeated her saying that “humility is truth.” That being so, a humble person treats himself and others as he should, with the respect that every human creature deserves. So the princely angelic, and humble bearing of this man of God spreads throughout his entire personality. The Gospel says that Our Lord’s tunic or cloak was imbued with virtue, a force that healed everyone who touched Him. That shows how much man communicates through his costume. Saint Odilo evidently could not be compared with Our Lord, but his cloak had a splendor that expressed his personality. Hence the dignity of each of its folds. You can imagine a medieval cloister made of Gothic arches, Saint Odilo walking alone in it, and a novice watching from a distance. The novice kneels as Saint Odilo passes by and blesses him. The novice keeps looking with admiration and later writes down the episode. That is how we have these impressions about the extraordinary personality of Saint Odilo, the model priest. “The Catholic Church is the only commendable thing I have found in my life” I want to rectify your idea of a model priest, so you understand well what a priest is according to the spirit of the Holy Roman Catholic and Apostolic Church. This is a eulogy of the priesthood more than a eulogy of Saint Odilo. More than praising the priesthood, I am praising the Catholic Church, which, with the grace of Our Lady, I will not stop praising to the end of my days. The Catholic Church is the only commendable thing I found in my life! All other things are commendable only in relation to the Church and insofar as they participate in her. So what I’m doing is to praise the Church. St. Odilo is an ideal priest, and the Church fosters that priestly ideal. So should be the priests of the Reign of Mary. He brought something luminous that invited imitation and veneration. The light of grace in him shone outside and manifested the quality of his soul, as a soul’s behavior appears in the attitude of the body. Let us speak briefly of its outward appearance. The indescribable luminosity proper to saints That biographer was very much into “Ambiences and Customs.” He knew to discern the luminosity in Santo Odilo and so many saints. It is something challenging to describe because it is a luminosity of the look, but more than that, a luminosity that surrounds the saint. You can see it very much in the painting of Saint Pius X belonging to the Santiago Group, which is now in my living room at the Seat of the Reign of Mary. It is worth going into the room and looking at it when you visit. While its frame is beautiful, it is not absolutely not decorative in that spot. Still, I decided to keep it there because I am encouraged and enthused to see his luminosity. It is not something just put on by the painter. Just as we distinguish a living person from a dead person and do not know how, neither do we know how to distinguish a deceased person from a sleeping one. Likewise, a saint’s light is distinguished from any natural radiation of a nonsaint’s talent. For example, St. Pius X’s painting has something indescribable that fills you with enthusiasm, satisfaction, and joy. Looking at him, we understand the indestructibility of the Catholic Church. So was the great St. Odilo. Harmonious opposites in St. Odilo’s soul He was of average height. His face expressed both authority and benevolence. The author emphasizes contrasts very well. He had just said that Saint Odilo had something that made you want to venerate and, at the same time, imitate him. It was not imposed veneration as if saying, “Know that I am like this and you are not” (which would be mega), but veneration that says: “I am like this, but Our Lord Jesus Christ is infinitely more than I am. If I must be perfect like Him, why don’t you try to be perfect like me?” It is an invitation to come closer, to unite, to rise. So was Saint Odilo. Here is another stunning contrast: he was full of authority and benevolence. The Revolution tries to make us believe that a man in authority is malevolent; he is a kind of beast who has risen and delights in seeing an opportunity to bludgeon others. It is as if he said, “I was beaten until I climbed, but now that I’m on top, I get even by beating others.” From the Catholic point of view, this is utterly despicable. No concept of authority can be thrashier than this. On the contrary, authority exists to do good. Its mission is to carry out benevolence. Benevolence means wanting the good of others and, above all, the good of the Church, of Christian Civilization, that the will of God is done everywhere, that Our Lady Reigns as Queen. And a desire for others to associate themselves with this good, to belong to it, and bring everyone to the good, preferably with indulgence, kindness, and mercy. St. Odilo expressed benevolence and authority to a high degree.

On the Holy Shroud of Turin’s gaze of gazes He was smiling and welcoming to kind people, but with the proud and rebellious he looked so terrible they could hardly bear his gaze. What a perfect and finished saint, what a wonder. Every saint is perfect and finished, but I am enthusiastic about this man’s weapon: his gaze. Few men possess this weapon. The gaze of gazes, the perfect gaze you will ever get to know, is a closedlidded, lifeless, dead gaze: that of the Holy Shroud of Turin. That countenance has no more life, and the eyelids are closed. Examine His gaze. No one has ever looked like that. Those closed eyelids look more than any look. Can you imagine Our Lord’s gaze at Saint Peter? The latter wept all his life until he died because he had denied Our Lord. I like to think that Our Lord’s last gaze on earth was not directed at the monsters assailing Him, nor at the holy women or Saint John at the foot of the Cross. I take it for granted that His last look was on Our Lady. If we only could measure His affectionate gaze to Our Lady, filled with love and respect, veneration, and mutual understanding! How did Our Lady return that look? How was their exchange of glances? In humanity’s entire history, that was the culminating moment in the history of gazes. Had someone managed to look at those two gazes, he would be in heaven and could go blind afterward. It might even be an advantage, for why see anything else after that? Anyone who had seen those looks had already seen everything and needed to see nothing else. Such is the value of a gaze. The man who wrote this knew how to see Saint Odilo’s terrible look. How admirable! He was terrible as an army in battle array, as was Our Lady. Thinness that is flexible and full of strength is a perfect antithesis, a wonder He had a form of thinness that accentuated his strength. He had an elegant pallor, and his white hair was a form of distinction. How beautiful, if seemingly contradictory. Because in a bullish conception of things, the more a man is heavyset, the stronger he is. So to have a kind of flexible thinness full of strength is a perfect and marvelous antithesis. Eyes used to shedding tears is something the modern world does not understand His eyes gleamed with singular brilliance that inspired both surprise and amazement. They appeared used to shedding tears because he had received the grace of compunction. Authority, gravitas, and peace emanated from his movements, gestures, and gaze. For someone to be approached by him was a delightful surprise, a ray of joy and grace. The modern world no longer understands this but only likes eyes used to laughing, foolish eyes that only reflect selfishness. The ancient world understood the value of eyes used to cry over holy things: Crying over the Passion of Our Lord, the sins of the world, and one’s own sins – how that brightens one’s eyes! Sacred weeping by great souls transforms a person’s gaze into something luminous like a cathedral’s rose window on a bright sunny day. Look how marvelous: St. Odilo approached someone praying in a room or chapel, bowed down, and said, “My son, pray for such an intention or do such a thing.” The person felt flooded with grace and had a delicious surprise. See how a priest is, according to the Constantinian ideal of the Church, the true ideal of the Church, and how we must venerate the priestly state and the true priestly ideal. He was perfectly self-possessed, with no form of adornment or trickery. Nature had made him something admirably harmonious and orderly. Saint Ambrose was right to say that the beauty of the body is not a virtue, but should we despise this gift of God because of that? That is a way of saying that St. Odilo was a handsome man and that his body’s beauty adequately symbolized the beauty of his virtue. Here you have part of the vast text on St. Odilo. If Our Lady allows it, we will study it point by point until the end.

Cluny, today |

|