|

Chapter 3

Centralisation:

A People vs. the Masses

|

|

|

From the exuberant life of a true people, an abundant rich life is diffused in the state and all its organs

With the barbarian invasions, the population density of the cities diminished greatly and small towns became completely isolated. This isolated economy obliged them to become self-sufficient and take advantage of everything within their locality. It was direct subsistence without any external commerce. In these conditions, each small community developed a unique character that developed its own architecture, its own dress, its own customs, and even its own language and dialects. By the 11th–12th centuries, Europe resembled a mosaic of tiny cultures that were small worlds unto themselves, each one bursting with life. Many of these regional variations yet survive. Indeed the principal attraction Europe exercises over tourists is the variety of regional dress, architecture, dance, music, and cuisine that are faint remnants of the varieties that proliferated in medieval times. Each region and town produced its own culture and civilisation that was distinct from the next, even if it were just a few leagues away. It is not hard to see that this proliferation of exuberant cultures was a grassroots movement: these were small communities where individuals and families naturally communicated their vigour and influence in an ambience where public authority was limited. It was a time when the individual, the family, and custom directed life more than the constituted public authority. Beginning in the 12th century this situation underwent a transformation, as feudal warfare diminished and Europe experienced relative peace. The knights-errant had cleared the thoroughfares of bandits and commerce had resumed. As the barriers between isolated communities disappeared, bigger towns were formed. Kings naturally emerged and constituted courts, and capitols began to appear in the various kingdoms. Everything began to tend toward centralisation. This centralising trend continued to gather force until the 17th century and the beginning of the 18th century, with monarchs like Louis XIV of France and others a bit before and after him, such as Philip II of Spain and Peter the Great and Catherine of Russia. This concentration of authority upset the natural interplay of influences and was most noticeable in the court of Louis XIV. It was the paradigm court. Its king, known as the Sun King, considered himself to be as kings should have been. He was surrounded by nobility who considered themselves to be the perfect model of courtly aristocracy. In fact, they were indeed imitated by aristocracies all over Europe. This court had statesmen Europe considered to be the most accomplished. It had great ladies who were the prototype of elegance, charm, and feminine beauty in that century. Even the Church participated in this movement, with ecclesiastics such as Jacques-Bénigne Bossuet, a bishop and theologian renowned for his sermons and other addresses. He was followed shortly thereafter by another bishop, Jean-Baptiste Massillon, both considered as model Church orators throughout Europe. Thus, a new centre was formed upon which the whole of France—indeed all of Europe, to varying degrees—modelled itself. This presented a state of affairs diametrically opposite to what had existed heretofore. Everywhere local influences disintegrated. Everywhere regional character gradually disappeared. They gave way to a new centre equipped with technocrats and specialists who were better at everything, from the art of conversation to the art of finances, from leading armies to directing the Church. Everyone imitated this new centre and the situation was entirely transformed. Life as well as social movement no longer came from the grassroots upwards, but rather from the top downwards. It no longer came from the social body influencing those at the head of society, but it is now those at the head of society moulding the social body, which has now become a lifeless mass and allowing itself to be totally dominated.

Contrary to appearances, this centralisation did not cease with the French Revolution. Indeed the Committee of Public Safety exercised greater centralised authority and power than Louis XIV. Napoleon had even greater power than the Committee of Public Safety. Many French historians and legal experts agree that today’s French heads of state have much greater means to direct the social body than Louis XIV had at the height of his glory. In this way, the interplay of influences had changed. With the transition from an aristocratic monarchy to democracy, the people were now king. In this directing centre, things had changed a bit. We now had what some sociologists have identified as a “doxocracy”: for each problem arising within society, a commission or quango—predominantly composed of specialists and technocrats—is established to find a solution, which is then spread, via the mass media, to influence the general public. Thus influenced, the electorate is free to choose; but the main impulse still emanates from the capitol. More precisely, we have technocrats who leave their respective centres of life and go to the capitol to imbibe an artificial life. From there they direct the propaganda and obtain, through elections, the necessary mandate to implement whatever they want. In this way, the capitol, with its peculiar values, continues to direct society from outwards in. All regional and local values gradually lose their influence and capacity to develop. The result of this process is the impoverishment of modern man. Each of us has the sensation that he is an isolated grain of sand within a multitude. We are gradually becoming so accustomed to reacting only to external stimuli (all means of social communication, primarily television, printed media, cinema, the internet, twitter, etc.) that we are renouncing everything that originates from within us and that projects itself on the outside world. We are passive and inert in face of the enormity of outside stimuli leading all of us where we know not; but if we did know, we would tremble. A typical example of how this influence works was illustrated by a full page picture in the magazine Paris Match (1966). There was a photo of a young lady dressed in a very masculine way and who was brandishing a club. Since her mother had been a movie star, the magazine had also published a photo of the mother when a young lady herself. The photo showed her to be very feminine at a time when women were proud to be so and when a man’s appreciation for a woman grew in direct proportion to her femininity. There is also a very masculine man at her side embracing her, presumably the father of the young lady. One could think that if the mother, who had been proud to be so feminine, could have foreseen that her daughter would turn out to be this strapping lad of the feminine sex, she would have fainted. One must ask how she was led to accept this in such a way as not to even perceive she had changed. It was precisely because of external stimuli: “This is the fashion now, so this is how it should be.” She did not reason the thing out; so, what was the consequence? She was completely transformed as a result of an unperceived cultural or psychological transhipment. Exercising an influence coming from without, the external stimuli gradually impose upon us, and within us, prototypes, fashions, and ways of being that can be in contradiction with our most profound tendencies. Pope Pius XII explained this situation very well in his famous Christmas Radio-Message of 1944: The state does not contain in itself and does not mechanically bring together in a given territory a shapeless mass of individuals. It is, and should in practice be, the organic and organising unity of a real people. The people, and a shapeless multitude (or, as it is called, “the masses”) are two distinct concepts.

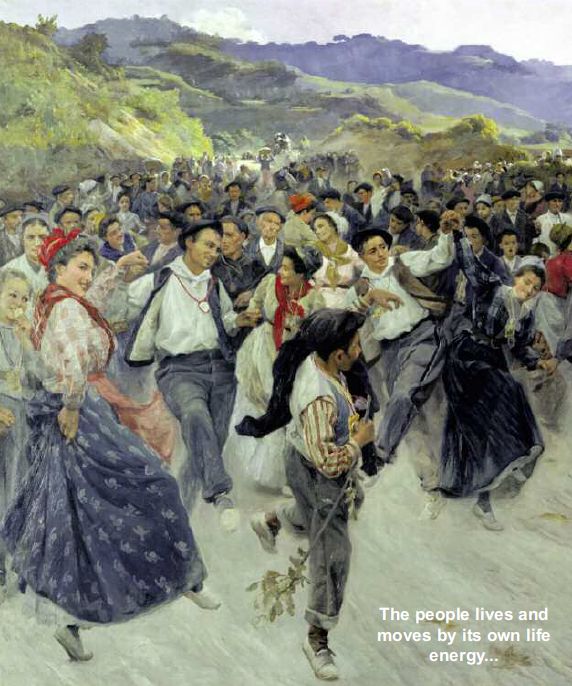

"The people lives and moves by its own life energy..." “Returning from the Calvario fair” (1903), Ignacio Diaz Olano. Fine Arts Museum of Alvara, Spain The people lives and moves by its own life energy; the masses are inert of themselves and can only be moved from outside. The people lives by the fullness of life in the men that compose it, each of whom—at his proper place and in his own way—is a person conscious of his own responsibility and of his own views. The masses, on the contrary, wait for the impulse from outside, an easy plaything in the hands of anyone who exploits their instincts and impressions; ready to follow in turn, today this flag, tomorrow another. From the exuberant life of a true people, an abundant rich life is diffused in the state and all its organs, instilling into them, with a vigour that is always renewing itself, the consciousness of their own responsibility, the true instinct for the common good. The elementary power of the masses, deftly managed and employed, the state also can utilise: in the ambitious hands of one or of several who have been artificially brought together for selfish aims, the state itself, with the support of the masses, reduced to the minimum status of a mere machine, can impose its whims on the better part of the real people: the common interest remains seriously, and for a long time, injured by this process, and the injury is very often hard to heal. |

|